Hips for Hauling, Shoulders for Shooting

The Mechanics Behind the Hip Belt

You’re 10 miles into your loaded ruck march; you have your hip belt cinched down. Both calves and quads are packed with blood, driving you forward. As you press forward, your heart and lungs are being put to task, boots sucking on the mud. You remember that the cool guys have told you to ditch the hip belt “it’s not necessary”, you ditch it to move faster. A few more miles and your spine, shoulders and hips start singing, there is numbness in the hands. The pack slowly begins to eat at your soul, you begin to fatigue and take one wrong step, you buckle to one side and your sciatic nerve lights up like a Christmas tree, shoulder goes dead. Suddenly you’re no longer training, you’re triaging your way back. Turns out that little buckle and belt isn’t an oversight by manufacturers, it can be the difference between completing the mission or winding up as a liability…

When moving with heavy load becomes a job requirement or an accoutrement for overall functional health and fitness, understanding the parameters of what is needed to improve conditioning for this task while reducing the risk of injuries can look like a bunch of road signs pointing in several different directions. A quick search online can leave you more confused or flat out armed with “bro-science”. Everything from, what boots, what pack, how to adjust it, hills vs flats, all play a part. As someone who has spent hundreds of hours with a pack on, treated countless soldiers and adventurers as patients from a plethora of load related injuries, I feel it is necessary to approach this from a biomechanical and peer reviewed perspective on what works, what doesn’t and what is downright dangerous. The oath I have sworn was to do no harm, and if possible, have a positive impact on the health of people. Today we are going to talk about the hip belt.

Carrying heavy load naturally increases force on the body. Every time you throw that ruck on, more compression, torsion, shear and inertial forces act on the body; thus increasing the stress on the ligaments, articulating surfaces, bones, muscles and of course the disks. Managing these forces appropriately is required to give one a fighting chance for longevity of this task.

The forces of rucking don’t discriminate; they hit everywhere at once. The spine takes longitudinal compression; shoulders can get crushed under straps and feet get pounded. It’s well documented, and I have seen first-hand that these forces can cause a wide range of injuries. ACL tears, labral tears, stress fractures, herniated discs, supraspinatus tears, rotator cuff tendonitis, thoracic outlet syndrome, sciatica which shoots like lightning, pudendal nerve shocks and even vascular shutdown. In garrison it’s risky enough, add combat environments and it goes up exponentially. As precarious as this activity sounds, it’s about using every tool in the toolbox to help manage and reduce risk down to safe levels. If done correctly can actually have a massive positive impact by improving one’s conditioning and strength of several systems of the body. That one underrated wrench in the toolbox is the hip belt, it’s been peer reviewed, battle tested, and criminally dismissed by every Big Sarge with a YouTube channel and zero PT tests. Here is the thing, the data isn’t opinion, it’s measurable, so let’s start with the most obvious one…the spine.

The Spine

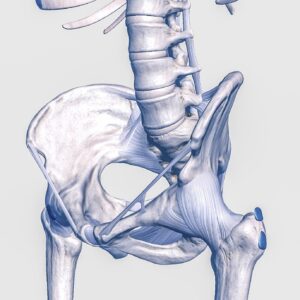

It’s pretty obvious that carrying a load through the shoulders puts force on the entire spine, but magnifies through its weakest link, the L5-S1 disc. This is the last spot in the upper body before it hits much stronger structures like the pelvis and femoral acetabular joints, which are better suited to manage these kinds of loads. What a hip belt allows for is a “bridge-redirect” of force, almost like a shortcut. Plain and simple the hip belt delivers a portion of force straight the pelvis and femurs therefor reducing force on the spine.

Back in 1985 a PhD researcher in Ergonomics and Physiotherapy out of New Zealand conducted a study of volunteers to haul gear in several different kinds of packs with up to 20 kilos. They studied the forces on the body using pressure sensors and metabolic gas analysis. They compared pack-only, to pack with hip belt. The peer reviewed analysis of data concluded that the hip belt funneled approximately 25% of the load straight to the hips, this further reduced the mid-stride compression on the L5-S1 disc by 28%. Without the hip belt forces peaked at 3,800 newtons. However, while using a hip belt these forces were brought down to 2,700 newtons. (Legg, 1985 Comparison of different methods of load carriage, Ergonomics, 28)

In another peer reviewed study from 99’ French Biomechanists took military cadets and loaded them with 35 kilos in a regulation ruck. Using motion capture cameras and force plates under treadmills, they filmed marching at various paces of gait. They observed that without a hip belt on average the forces spiked up to 5,400 newtons, flirting with damage thresholds, this magnitude of longitudinal force spiked disc pressure and potentially caused excessive shear on the facet joints of the spine. When they added the hip belt forces dropped to 3,700 newtons a 32% reduction while stride stayed clean. (Vacheron et al., 1999, Influence of hip belt on spinal loading during military marching, Journal of Biomechanics)

In 2013 researchers from the UK had fit males loaded with 40 kilos to study muscle recruitment and exertion with and without a hip belt. Using inverse dynamics and EMG studies they found that without the belt, the spinal erectors output had jumped 30% harder for the same amount of force. Imagine what this does over time pushing through mile 10. They found that not only were the muscles working harder to compensate, they also measured an increase in spinal compressive forces at the L5-S1 disc to increase by 15%. The final nail in the coffin was that without the belt, they observed that gait began to show fatigue after only 20 minutes. (Stuart, et al. 2013. The influence of hip belt design on spinal loading during load carriage. Journal of Biomechanics)

Three decades, three countries, peer reviewed, same verdict.

The Shoulders

Even from a young age, we’ve slung bookbags over our shoulders, our backpacks jammed with textbooks, like rounds in a magazine and told to march. We all know the feeling of those traps screaming after three blocks. We have been told that you just need to get stronger. Indeed, this may be the case, but how strong? Strong enough to carry 100 pounds solely through the shoulders over 10 miles? That’s not getting stronger, that’s begging for nerve death and busted joints. Your shoulders were never built for this; they’re not pillars, but pivot points. They can adapt and carry loads, but everything has its breaking point. Just like in the spine, when you force a ton of weight through those weaker joints without the redirect, you’re asking for a nerve compression, and soft tissue damage. Forcing weight through the shoulders without the redirect will increase the risk of compression of the brachial plexus, compressing the subclavian artery and shredding tendons. Clip in the hip belt and hand the war back to the pelvis.

Back in 2006, a team of Neurophysiologists from South Korea wired up military aged, fit males with electrodes for a nerve conduction study. Their goal was to understand the forces on the brachial plexus under ruck stress. Each candidate was loaded with a 30% pack to body weight ratio (45-60lbs) without a hip belt and had them march. They observed that 40% of candidates showed nerve conduction slowing; their thoracic outlet was clamping down on the nerves like a vice, mimicking TOS (thoracic outlet syndrome). Hand sensations and dexterity crashed, amplitudes dropped between 30-50%. Grip strength also dropped 25%. Blood flow was also an issue through clinical findings of ischemia; this was tied to the subclavian artery compression. When the weight belt was added back, all metrics normalized. (Kim et al., 2006, Brachial Plexus Lesions after Backpack Carraige in Young Adults, Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research)

The US Army funded a study headed by Dr. Bruce Knapik, the legendary ergonomics guru who’s spent 30 years dissecting soldier breakdowns. Across eight field trials and 250 active-duty soldiers, hauling 20 kilo rucks on uneven terrain, he zeroed in on one variable, the hip belt. They measured shoulder pressure using sensors and tested blood enzymes for rotator cuff damage, which indicate soft tissue damage. They concluded that with a belt, shoulder pressure decreased by 28% and enzymes dropped 35% (Knapic, et al. 2004: Soldier load carriage: historical, physiological, and medical aspects, Military Medicine)

Later in 2015 Dr. Knapik and his team tracked 1,200 Army recruits during basic training. Using a 35% ruck to body weight ratio (50-70lbs), his team wanted to understand the effectiveness of a hip belt. Without the use of the belt redirect, peer reviewed data showed a massive increase in rotator cuff injuries 28% higher by recruits in the first 8 weeks. Tendonitis, impingement, early tears and a significant uptick in trapezius myalgia above 34% was shown in the group not using the hip belt. Knapik didn’t guess, he just counted bodies. (Knapik, Orr, Pope, et al. Risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries in military recruits during basic combat training: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 2015)

Your shoulders aren’t meant to be shock absorbers; they’re meant for buttstocks.

Metabolic Factors

Shouldering a ruck in training should be considered an opportunity for hard earned growth, not a burden. A ruck in combat should be considered an asset, not a liability. The body doesn’t care what you call it. The only thing that matters to it is heartbeats per mile and the hourglass until collapse. Skipping the belt shrinks the hourglass, with the belt, you get a tax refund. Arrive after the movement fresher, or on a litter.

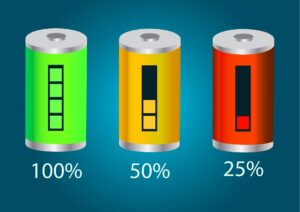

In 2017 American researchers conducted a study on the effectiveness of hip belts with regards to exhaustion while marching. With a load of 20 kilos and no belt on the subjects, they noticed an average of a 10bpm increase in heart rate over baseline. They observed an additional 8-12% metabolic cost increase, measured by bpm and VO2. The pack without the belt acted like parasitic drain on a battery. (Carmy, et al. 2017. The Effect of a Backpack Hip Strap on Energy Expenditure While Walking)

The US Army took field data from 200 soldiers who were studied during marches carrying 15-25 kilos over 5–12-mile marches to determine the effects of energy wastage over baseline without a hip belt. They recorded a 12-18% increase over baseline by mile three. Lactate levels passed the anaerobic line 20 minutes faster than belted groups. Additionally, there was a 25% higher failure rate in the unbelted group. We’ve all been there, bent over, hands on knees, heart thumping, clearly an ineffective soldier not showing up for the fight. (Knapik, Reynolds, Harmon. Soldier load carriage: historical, physiological, biomechanical, and medical aspects. Military Medicine 2004)

In more recent years British DoD scientists, think Q from 007, but with instruments not gadgets, put active-duty troops through an extreme 2km loop over rocks and hills while rucking 25% of their body weight, with an issued Bergen. They used gas analyzers for measuring metabolic rate, EMG’s for muscle activation and high-speed motion cameras for gait breakdown. Without a belt, VO2 jumped 14%, their traps and lats were punished, 21% lats, 28% traps with an entire shoulder girdle increase of 25% in expenditure. End result, the fatigue set in 12 minutes early. Same men, two options, clearly a different outcome. (Teo, et al. 2022. Load redistribution via hip belt modulates metabolic cost and muscle fatigue in prolonged walking. Journal of Experimental Biology)

Hip Belt Doctrine

It’s 1953 a man wearing glacier glasses is crossing the Kumbu Ice Fall, he slings his 80lb canvas pack without hip straps onto the snow, he leans up against an ice shelf and takes a breather. He looks past the crevasse field and sees the Western Cwomb; Lhotse to the right. To the left, he sees the ankles of Everest. His name is Sir Edmond Hillary. Tomorrow, he pushes higher into the unknown. Tonight, he will be suffering, shoulders throbbing, back aching. The higher he goes; it just gets worse. He doesn’t know about hip belts yet, they didn’t exist. Just man negotiating terms with the mountain, fueled by the goal and hydrated by determination.

It’s 1956, the sixth summit, a Swiss team sewn leather pads into their packs, the padded hip belt was born. This design reduced shoulder stress by 10% and would cut the path for all modern designs, a massive leap forward for the time. In Vietnam, they began using hip belts for radio operators carrying PRC-25s, buckled low so they could still sprint when Charlie popped.

In the decades that followed, two tribes formed. One camp said “wear it as a spine saver”. The other camp said “ditch it and don’t get tangled”. They were both half-right, and both completely blind; the reality is its ALL situational dependent. The belt is a switch, not a scripture.

So, when to belt, when not? Simple, wear it when the terrain tries to own you, unclip before the enemy even thinks about it.

The goal here is to be combat effective, if year two of service herniates your L5-S1 disc, you’re not battle hardened, you’re now paper pushing. Not to mention your injury “is not service related”. Here’s the deal, wear the belt every safe chance you get, PT, long infills, uneven terrain. In high-risk environments, think falling down a ravine or contact likely scenarios, unclip, you may need to drop that ruck in a hurry to fight the enemy.

Verdict

The results are in, and have been sitting in dusty journals for decades. Hip belts don’t just help, they tilt the scales on combat effectiveness. We have seen an average reduction of: 25% spinal compression, shoulder loading 25-35%, and metabolic cost savings of 12%. The belt isn’t perfect, nor is it magic, but it’s just enough that soldiers walk out rather than being wheeled out. The guy who says “man up belts are for the weak”, never had to explain to his wife why he can’t pick up his kid. Let’s not forget that dogma will always be loudest, but hasn’t a fighting chance against the data. Empirical evidence doesn’t shout, it doesn’t need to, it just wins, EVERY…DAMN…TIME.